Although creative types are loath to admit it, a charismatic front man with business acumen is often the key to success.

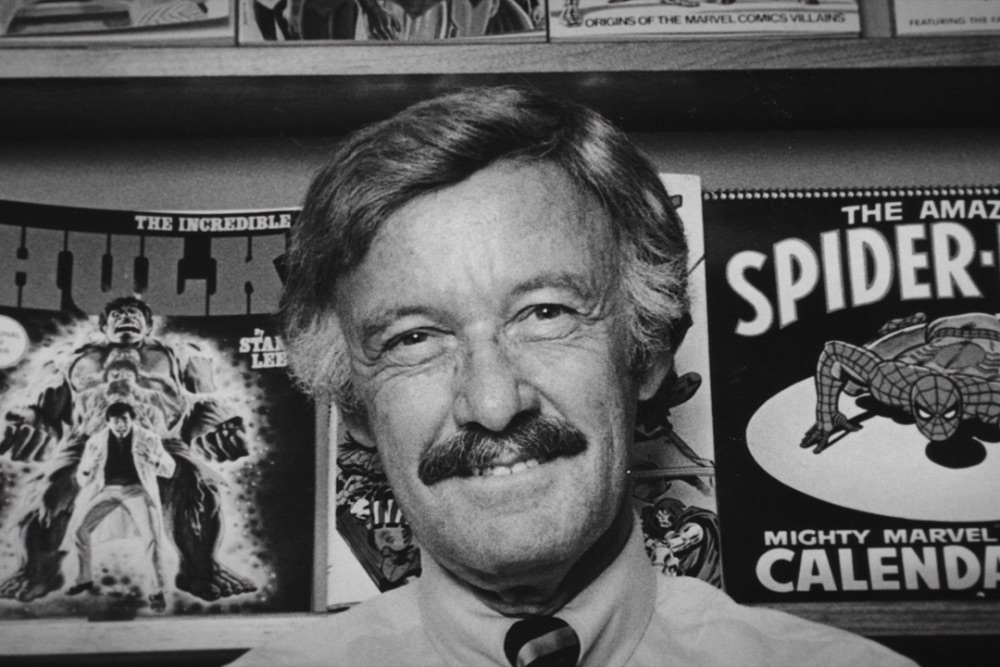

If your interest in comic books runs deeply enough, you’ve probably read about the ‘Marvel method’. This was Stan Lee’s invention-of-necessity approach to producing comics during the 1960s. In short, rather than write detailed scripts and pass them onto the artists, he would give the likes of Steve Ditko and Jack Kirby a vague idea of the story and characters he had in mind. They would then go off and produce drawings based on that and even suggest dialogue. Lee would come in later to recommend revisions and write or rewrite the text as he saw fit. This removed production bottlenecks and allowed a comparatively small creative team to produce large numbers of comics on a shoestring budget.

Due to this approach, the artists were in effect co-creators of Marvel’s golden age titles, among them The Incredible Hulk, The Amazing Spider-Man and The Fantastic Four – something Lee acknowledged in his autobiography many years later. In 2025, however, you will find social media accounts dedicated to exposing Lee as a hack; a charlatan who stood on the shoulders of artistic giants and claimed the credit for himself.

In addition to being a lifelong Marvel Comics fan, I’ve worked in numerous creative publishing houses and I believe I can provide some much-needed behind-the-scenes context that those hellbent on tearing down Lee’s legacy probably don’t have (or don’t care to share).

My first remark might come as a shock: At some point, publishing has to become a dictatorship.

Now, publishing anything – from a daily newspaper to a yearly almanac – must also be collaborative. A good editor (especially in magazines) will delight in other people’s talent, both written and visual. He will be open-minded and seek his colleagues’ opinions and ideas. He will be humble and honest with himself.

But in the end, he will have the final say.

Because no truism ever contained more truth than, “A camel is a horse designed by a committee.” It applies to any creative endeavour. If you don’t have an individual providing vision and focus… well, blindness and blurriness will be the result.

So often, too, creative success is about chemistry. You see it again and again, be it in publishing or television or music. Remove one person from the equation and the lightning you’ve captured together escapes its bottle.

Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko were talented men, no question, but even though they both went on to have careers after their collaboration with Lee, I doubt anyone outside the nerdiest circles of comic book fandom could tell you a single thing they created. Kirby possessed some scripting ability, but Ditko’s writing was dense and impenetrable and it was as if he’d never heard a regular person talk before. How much he and Kirby contributed to the text is, in a sense, immaterial anyway. Stan Lee was the editor and he guided the creative direction for those early comic books. He had the final say and their newsstand success or failure was on his head.

Here’s something else creative types don’t like to admit: every creative project needs a salesman.

Stan Lee was a born salesman. He loved to talk to people, he loved the camera, he loved to spruik Marvel products. As his wife put it, he loved being Stan Lee. He was charismatic. He exuded a unique brand of enthusiasm and mode of speaking that broke through in both televised and printed interviews.

Introverts – and most writers and artists are by nature introverted – tend to envy such people to the point of loathing. That ought to be me up there, they fume. I’m the talented one. He’s nothing without me. Why should that jerk get all the credit?

Maybe there’s some truth to that sentiment, but it’s a whiny, piss-into-the-wind truth. Because every successful creative project, whether it’s a $500 million movie or a 25c comic book, will have a decisive or charismatic figurehead calling the shots. Sure, Stan Lee was a raging egotist. That’s exactly who you want promoting your company and its wares.

The criticism directed at Stan Lee – that he took credit for other people’s achievements – has also been levelled at people such as Steve Jobs (Apple) and Elon Musk (Tesla, Starlink et al).

It’s true that without Steve Wozniak’s engineering nous Apple would never have existed, but it’s also true that without Steve Jobs supercharging Apple’s production and promotional engines, it likely would have been just another flash-in-the-pan tech company. And it’s not as if Elon Musk sits in his office designing the next electric car or rocket, but without his broad ambition and hard-nosed pragmatism providing drive and direction, none of his companies would be where they are today. He’s not the world’s richest man by accident.

As unintuitive as it seems, the friction that develops between creativity and business often leads to superior outcomes. Most people would agree, for example, that music isn’t what it used to be. There was something special about albums produced in the period between 1965 and 2005, a quality that didn’t exist before and hasn’t since. I would argue it was the armed truce between creative freedom and commercial profitability. Musicians always wanted to try something original and push boundaries, which was terrific until their songs became self-indulgent and esoteric. On the flipside, the labels wanted ‘radio friendly’ music the masses could digest to maximise profits (and ultimately it is a music business), but this mindset kills creativity, leading to homogenisation and ultimately stagnation. It was the push-pull between these two forces that charged the music industry’s batteries for a good 50 years.

The corollary is that sometimes an artist gets so popular and financially successful he or she is no longer subject to that friction, and the results are often dire. The author Stephen King is perhaps the quintessential example. In the 1990s, he arrived at a point where his books were such guaranteed bestsellers he could contractually demand his preferred collaborator, Nan Graham, edit his books instead of an independent editor assigned by the publishing house. It’s no coincidence that the quality of his novels has diminished steadily ever since, to the point where his post-2015 releases are nigh on unreadable.

As my first boss once said to me, “Everyone needs an editor, especially the editor.” When you don’t have that objective voice, someone who will speak truth to power or make you justify your creative choices, you become sloppy and lazy. Brilliant work is seldom created in an ivory tower.

Pointing out that Marvel performed better financially when Lee wasn’t in charge (as some commentators have done) is preposterous Monday morning quarterbacking and denies the simple reality that any success Marvel later achieved was built on the back of Lee’s imagination and the talented artists who brought his visions to life. Those in the Marvel ‘bullpen’ probably didn’t get the credit they deserved for their creative contributions, but Marvel would never have become a publishing juggernaut in the first place without Lee.

Condemning Lee’s prose as purple and excessively alliterative 60 years after the fact is another intellectual cheap shot (the literary equivalent of offense archaeology) – and even if the criticism is valid, it’s irrelevant. Lee’s 1960s audience lapped it up and it became his signature style.

Oddly, the merit of Lee’s writing is beside the point as well. His true masterstroke lay in his ‘Stan’s Soapbox’ column and his interaction with fans. He perceived that a successful comic book company wasn’t about him or the artists; it was about the readers. Lee made Marvel readers feel they were part of a special club and that, as much as the generation-defining characters in the pages of the comics, was what set Marvel apart from its competitors and entered it into the zeitgeist.

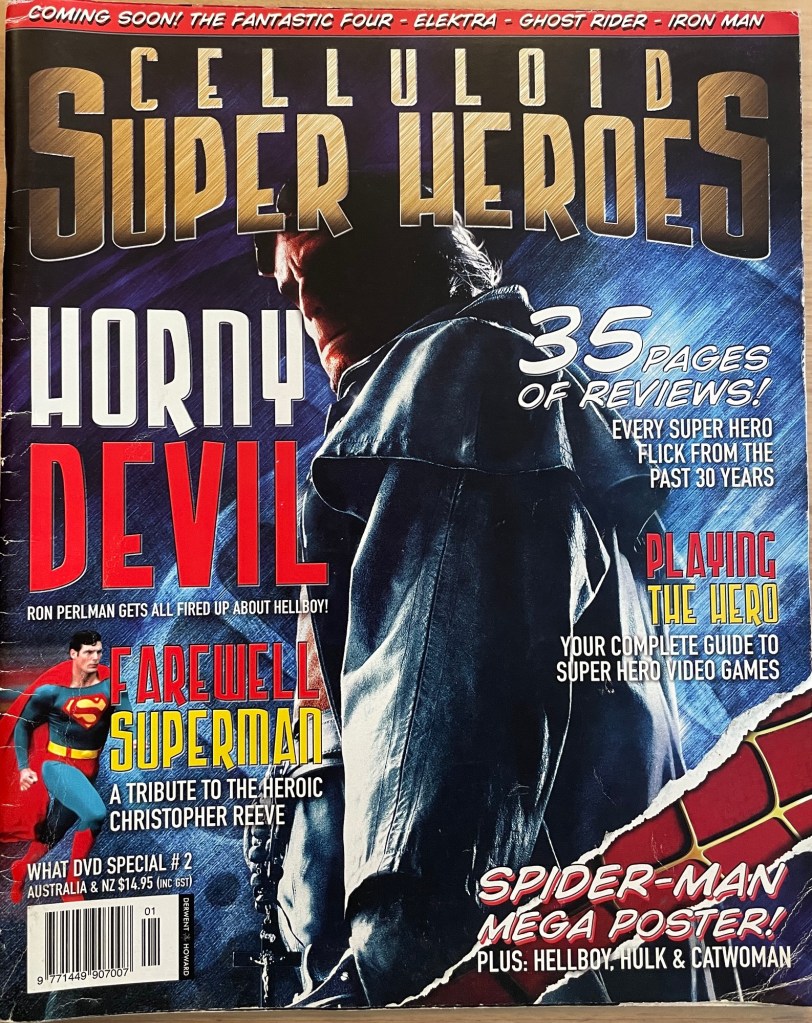

Twenty years ago now (God help me), a publisher tasked me with creating a one-shot magazine about superhero movies. That was the extent of the brief. “Superhero movies are popular right now, take this tiny budget and go make a magazine about them.”

If someone were to pick up a copy of Celluloid Superheroes today, he or she would tally my contributions (an editor’s column, a handful of reviews and a few other items) and justifiably assume I had little creative input. But the title originated in my head. So did the parameters and scope (a review of every superhero movie made in the past 30 years plus supporting features and interviews). So did the rating system (separate evaluations on each movie as a standalone feature and as an adaptation of the source material). So did the last-minute decision to include an obituary on the recently deceased Christopher Reeve. So did the choice of cover image (Hellboy). So did the concept of including A2 comic book movie posters in the centre. And so on.

It’s not as if I had a deputy or editorial assistant to look after the day-to-day production requirements, either. Sourcing DVDs to review, commissioning and editing copy, and obtaining images from the studios were my purview as well.

Celluloid Superheroes proved a big success for the publisher and it remains one of my proudest achievements. I didn’t (and couldn’t have) done it alone. A band of talented, enthusiastic and poorly paid freelancers helped develop my ideas and produce the copy, while a creative designer gave the magazine its visual language and style. But would Celluloid Superheroes have existed without me? No, at least not in the same form. And that’s the salient point to take away from this parting anecdote. Marvel Comics might have emerged in some fashion even without Stan Lee calling the shots in its formative years, but it wouldn’t have been the same company without him.

I guarantee it.

Leave a comment