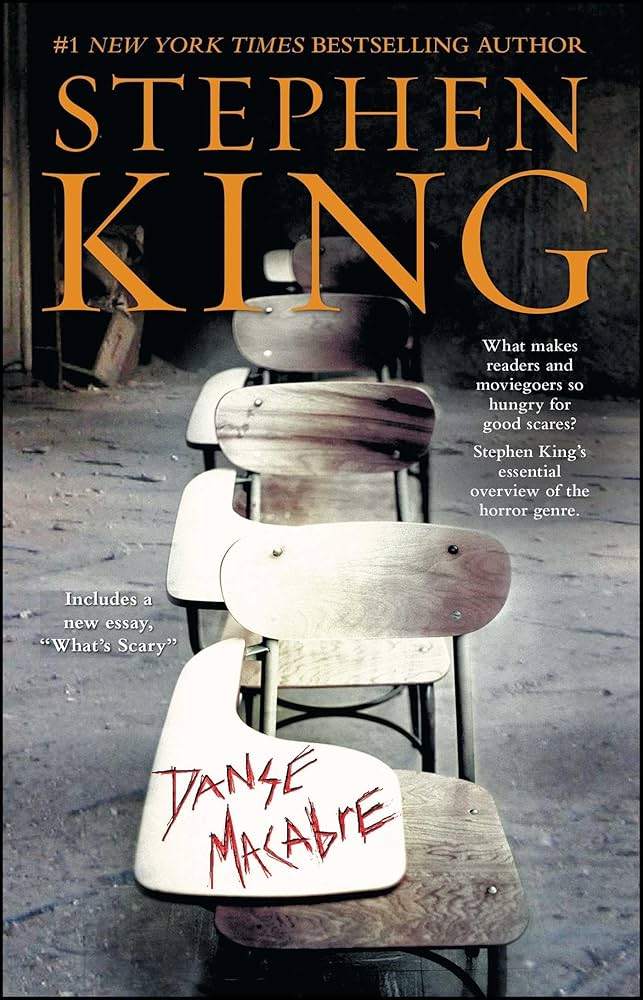

An awful lot of high-flown ideas are attributed to the horror story and if you’re interested in availing yourself of them, I highly recommend Stephen King’s book on the subject, Danse Macabre. The most commonly repeated one seems to be this: the small, controlled horrors in fiction or movies help us cope with and understand the real-life ones.

I find this assertion absurd.

Between 2010 and 2024, my wife Kellie and I have endured a surfeit of true-life horrors. Her mother died from leukaemia, her father and brother were diagnosed with bowel cancer (but survived), she developed multiple sclerosis, her father committed suicide, and, this year, Kellie underwent three brain surgeries that left us both physically and mentally frayed. During this decade and a half spent going through the wringer, it became clear to me that experiencing imaginary horrors has almost nothing in common with enduring those that befall us in real life.

Good horror fiction, like any other fiction, can take a reader away and make him forget his woes for a while. It can also serve as an allegory for something else, make the reader ponder the nature of existence, speculate what (if anything) comes next, push the boundaries of imagination. But even though I’ve read dozens and dozens of horror novels over the years, none could prepare me for my mother-in-law’s slow demise from blood cancer or made it any easier to put my dead dog in the back of my car while ants crawled up my arms. Conflating the two (as so many journalists and armchair psychologists have over the years) and claiming that horror fiction is an unhealthy interest is, at best, ill-informed.

Writing about horror and experiencing it for real are as disparate as writing about sex and actually having sex. I suspect some horror writers have tried to attribute a higher purpose to their fiction because reporters and critics so often back them into a corner and demand to know why they write such awful things. In their eyes, “because it’s fun and entertaining” is as an inadequate answer. Even someone like Bret Easton Ellis, whose novel American Psycho was primarily about style and subtext, found himself having to defend his use of horror.

I find it curious indeed that interviewers want to know why authors fashion make-believe and often fanciful horrors, yet have no qualms or queries about the realistic atrocities depicted in so-called ‘literature’. No one queries the fictitious cruelty in The Grapes of Wrath or the wanton murder in The Godfather or the realistic depictions of racism in everything from Uncle Tom’s Cabin to Crazy in Alabama. Horror fiction shouldn’t need special dispensation or a practical reason to exist, and horror writers need to stop apologising, stop rationalising, stop justifying what they do. Did Mark Twain write about racism in Huckleberry Finn because he was a galloping racist? Of course not. Same goes for horror. It is as valid a form of literature as any other.

Horror fiction is escapism. I’ve just finished a short horror story – the first composition I’ve managed for months – and I can assure you reading and writing about horror is the polar opposite of experiencing it in real life.

Leave a comment